"What is good thinking?"

I confess I looked blankly at my friend who asked me this question last summer. My brain brought back the answer, "You know, thinking well," and I choked it down. In the moment, I couldn't think of a suitable answer to such a simple question.

You're probably better than me! Here are three lines for you to collect your thoughts. What is good thinking?

In our first instalment of this guide, we collected notes, gave them titles, and organized them into clusters of information. I propose that thinking happened at each stage of the process, where we

- wrote the note

- titled the note

- changed the titles to organize the notes

- brought the note content into our example letter and

- edited the letter for readability.

Good thinking, at each of those stages, then, is a kind of understanding.

- Note Writing - understanding the idea we were trying to capture in a way that we can combine it with other ideas later. Not including irrelevant detail or leaving out important aspects.

- Note Titling - understanding where we'll look to find the note later.

- Note Organization - understanding how notes relate to each other.

- Note Selection - understanding which notes to bring into a project to provide the context and detail required for our audience to understand what we're trying to communicate.

- Note Combination - understanding how to organize note content to best communicate.

Using this context, we can imagine good thinking as a process of better understanding our world and how to communicate about it.

Understanding our World

Did you know that information overload is something we've been complaining about since the 1500s? The earliest known example (though possibly there were more even earlier, which became lost in history) comes from Erasmus who railed against the "swarms of new books" he battled.

I sometimes wonder what would he have made of cable tv news, the internet, and social media?

For those of us drowning in more information created in an hour than a year of Erasmusas's 1500s Europe, understanding our world seems like a fool's errand. Just search for what you need, when you need it, and don't worry too much about everything else.

Except for one thing: connection creates meaning. The more deeply we connect our ideas, values, information, activities, goals and dreams, the more wonderful life seems.

Living a shallow life without proper connection puts meaning completely out of reach, turning us into a generation always seeking meaning and only finding Netflix.

So, I propose that a significant part of good thinking is about making sense of all this content that's flowing past. In fact, slowing down and making sense of even part of it helps calm our anxiety and put us on a more profitable path.

The simple effort of picking out one idea from a blog post you read, a podcast you heard, a video you watched, etc., capturing it and labelling it (so it falls into a hierarchy of ideas like we did in our initial post) is a terrific start.

But let's take it one step further.

Connection Structure MVP

Somewhere on your note, you could think about the relationships between your pieces of knowledge. You could start elaborating. Or arguing. All you probably need is a bit of structure to get going.

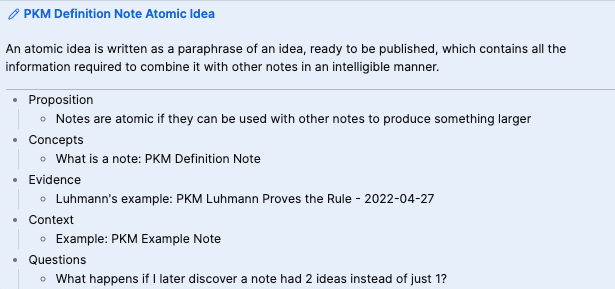

My suggestion for this structure comes out of experimenting with 4-5 various structures before I landed on this one. I stick with this one because it helps my productivity1. Every note I create has these 5 points somewhere in it:

- Proposition

- Concepts

- Evidence

- Context

- Questions

I use this mostly by connecting other notes where they fit into this structure. When I make a connection by linking to other notes, I write a sentence or two explaining the connection I see. Coming back to notes months or years later, this short explanation orients me quickly, reducing the time required to puzzle out previous insights.

Sometimes I don't have an external source note; I just have my own thoughts. I write them in. Later, those thoughts sometimes turn into their own notes.

Let's go back to a previous example note and see how this might look.

Although this is a contrived example, it is already extremely close to how I have taken over 4,000 notes. Elements to notice:

- The text after the colon is the title of a note in the collection. For physical notes with limited space, using a reference number like 3241-2b-67 is effective. With software packages like Obsidian, this title is a dynamic link which changes if the title of the note changes.

- Not every category gets an item every time. Many times I connect a lot of concepts while other categories are empty.

- "PKM Luhmann Proves the Rule - 2022-04-27" is an actual note from my collection.

- In my personal notes, I use a digital program, so instead of a text title of the linked note, I see a clickable link. This is useful because years later, a click brings me back to the note (which I've usually forgotten) and I can re-discover the note and its connection.

- As I collect ideas (notes) around an idea (note), I gain a deeper appreciation of how it connects to my growing understanding of a topic.

- In my personal notes I like to add the date I made the note to the end. I like to tell, at a glance, how old a note is.

One reason I use this structure is because of in the book The Craft of Research2, the writers offer an archetypal paragraph structure for academic argument paragraphs as a series of questions to ask.

- What do you claim?

- What reasons support your claim?

- What principle (warrant) justifies connecting your reasons to your claim?

- What evidence supports these reasons?

- How will you acknowledge alternative/complications/objections to your knowledge claim?

The book describes how each paragraph should contain certain types of sentences in a particular order:

- less general ideas either helping the audience understand the problem or pulling multiple ideas together;

- descriptions, summaries or overviews;

- concrete evidence, data or information with little explanation;

- (optional: more general ideas, like at the start of the paragraph);

- general abstractions which point toward a solution or conclusion.

You may not be writing academic arguments formatted as structured paragraphs, but these questions will help you produce much better arguments in your writing.

What's Love Got to Do With It?

You've probably noticed that when we fall in love, our thoughts rarely move forward. Far more commonly, we end up in rumination cycles, looping endlessly around a small set of topics.

Honestly, a lot of our thinking is far more like being in love than some Greek philosophical ideal of perfect rationality: moving through arguments and syllogisms to arrive at iron-clad conclusions.

This is where having a structure for linking our notes helps. The structure pushes us to think more broadly and critically.

One of my favourite teachers, Rintu Basu, once said, "It's okay to talk to yourself as long as you don't invite yourself out to the parking lot for a punch-up."

Taking notes with this proposed structure allows you to talk to your external brain - the collection of knowledge you've stored in your notes. And to your current self. Or to your past self. Even to your future self. You can argue with yourself, too! Just don't take it so far the police get a call from concerned neighbours!

Thinking Tool Proposal

In the first instalment of this guide, I proposed the primary goal of taking notes is really about producing content. This instalment expands note taking to include improving thinking and producing content.

Collecting information is fun, like collecting buttons, old license plates, or empty beer cans. Organizing collections is fun, a tough mental challenge. Linking notes is fun; what pretty graphs we can create!

The goal of note taking is none of these things.

Our north star is creativity in our thinking and output and sharing that creativity as broadly as possible. Growing collections without a corresponding growth in output indicates either a research phase or we've wandered from the path.

In the next instalment, we go beyond the process of collecting or using notes to one of maturing notes over long spans of time.